WHAT’S UP GLOCK?

Yesterday the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Florida’s “Docs vs. Glocks” law. This law is supposed to prevent doctors and other medical professionals from asking patients whether or not they own guns. In reality, the law does something different. Here’s the law, as summarized by the opinion:

[L]icensed health care practitioners and facilities (i) “may not intentionally enter” information concerning a patient’s ownership of firearms into the patient’s medical record that the practitioner knows is “not relevant to the patient’s medical care or safety, or the safety of others,” § 790.338(1); (ii) “shall respect a patient’s right to privacy and should refrain” from inquiring as to whether a patient or his or her family owns firearms, unless the practitioner or facility believes in good faith that the “information is relevant to the patient’s medical care or safety, or the safety of others,” § 790.338(2); (iii) “may not discriminate” against a patient on the basis of firearm ownership, § 790.338(5); and (iv) “should refrain from unnecessarily harassing a patient about firearm ownership,”

A group of doctors challenged this law on the basis that it violated their First Amendment right to freedom of speech, since it prevented them from asking or speaking to patients regarding gun ownership. The NRA supported the law, claiming that it kept doctors from “advancing a political agenda” against guns, by badgering their patients or telling them that guns are bad in some way. In reality, the law does something different, which I’ll talk about later. But first, here’s how the 11th Circuit came to find that the law is constitutional:

First Amendment Issues and a Diagram:

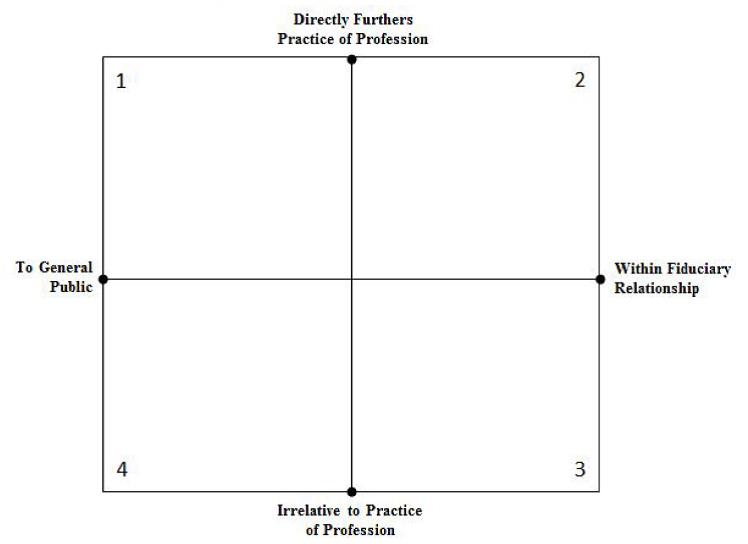

The 11th Circuit, voting 2 to 1, held that the law did not violate the First Amendment rights of the doctors. The court divided a professional’s speech into four broad categories:

- Speech to the public that directly furthers the professional’s practice (like giving a speech at a professional convention);

- Speech to a client or patient in furtherance of the professional’s practice (like asking a patient about their health);

- Speech to a client or patient about something that has nothing to do with the professional’s practice (did you see that game last night?); and

- Speech that’s completely unrelated to the profession and happens outside of any professional-client relationship (speaking at an NRA rally).

The court actually then drew a diagram:

The court also held that the closer the professional’s speech gets to the “professional interest” side of the spectrum, the stronger the government interest in protecting the public (and the more power the government has to regulate speech content), and vice-versa. So the closer a professional’s speech gets to corner 2 in the diagram, the higher the government’s interest gets, and so the more leeway it has in regulating the content of the professional’s speech.

In essence, the court ruled that the ability to regulate the content of doctors’ speech (not being able to ask patients about guns) goes hand-in-hand with the ability of states to regulate professions in order to protect the public interest.

The court ultimately found that the law was subject to intermediate scrutiny – not strict scrutiny – under a First Amendment analysis. Think of strict scrutiny as the hardest test possible that a law has to pass to be constitutional. Intermediate scrutiny is less hard, and only requires the law to:

- directly advance a substantial state interest; and

- not be broader than necessary to serve that interest.

Because the regulation of professions and the protection of patient privacy are substantial state interests, the court found that the law passed the first part of the intermediate scrutiny test. Since the law only applies to unnecessarily or non-good faith actions by a professional, and applied to any discussions or record keeping about guns (i.e. it doesn’t just prohibit doctors from saying that “guns are bad, mmmmmmkay”) the court also found that it was narrowly tailored.

One judge dissented, saying that the law violates freedom of speech. The dissent also took issue with the majority’s diagram, because

[i]t diminishes the First Amendment protection afforded to professionals by permitting the State to silence professionals on whatever topic the State sees fit.

The dissent is very much worth reading. My guess is that this case will be taken up by the U.S. Supreme Court, and we may get a ruling on whether or not states can regulate professional speech.

Another Consideration:

How in the world is this law, as a practical matter, going to be enforced? Let me show you what I mean by breaking it down into something more direct. To violate this law a doctor, nurse, etc. has to do one of these things:

- Intentionally enter gun ownership information into a patient’s chart that the practitioner knows isn’t relevant to the patient’s medical care or safety, or the safety of others; or

- Ask whether or not a patient owns firearms without a good-faith belief that the information is relevant to the patient’s medical care or safety, or the safety of others; or

- Discriminate against a patient on the basis of gun ownership (?); or

- Unnecessarily harass a patient about firearm ownership.

So to violate the law a medical provider has to act intentionally, without a good-faith belief, or unnecessarily. These are all very squishy standards that cut in the medical provider’s favor. Here’s how questioning about this would go down:

Attorney: “And doctor, did you in fact have a good-faith belief that the information about Mr. Patient’s gun ownership was relevant to his medical care / the safety of others?”

Doctor: “Of course – Mr. Patient has (kids / a spouse / taken antidepressants in the past / sought counseling at some point / poor eyesight / diabetes / high blood pressure / some other medical issue) which, in my medical expertise and training, led me to have a good-faith belief that simply asking Mr. Patient about gun ownership was relevant to his medical care / safety / safety of others.”

Any medical provider accused of violating this law isn’t charged with a crime, they’re brought before the Board of Medicine where the Board’s attorney has to prove that the medical practitioner violated the law. The standard of proof is much lower than in criminal court, but it’s still an uphill battle. Also, considering that the Board of Medicine (which is mostly composed of medical professionals) has to make the call, they’re going to be inclined to defer to the medical professional’s judgment.

And I didn’t forget about the discriminate or unnecessarily harass part – but really – how is the board going to prove a medical provider discriminated on that basis, or unnecessarilyharassed a patient? As a medical provider you can harass a patient about gun ownership, you just can’t do it unnecessarily. Come on.

So we’ll have to wait for the Supreme Court to have the final say, if my hunch is correct. But in the meantime doctors in Florida can’t (maybe) ask about your guns if they don’t have a reason that they can think of.